Moving Cattle- An Art and a Science

From the Block to the Saddle

March 12, 2021It seems like an easy task: getting a cow or group of cows from point A to point B. In reality though, this can be one of the most stressful jobs on any working ranch if you are not well versed in handling livestock or if your horse is not in the right position! Often times we find ourselves over complicating this action and over-correcting, leading to the target cow(s) fleeing in a direction undesired, making what should be a fast and easy job one that can take far longer. Do not worry though, this very thing happens all the time to even the most seasoned cowboy! Anyone who says they can move a cow(s) exactly where they want, one hundred percent of the time, is a liar! This post is designed to give a basic synopsis of how to set you and your horse up for success when working livestock. Whether in the show arena or the open pasture, the basics are all the same.

Lets start off by discussing cattle behavior:

All bovine are prey animals by nature, especially cattle. Over time, the species has developed behavioral patterns that better protect against predators which often is referred to as “herd instinct”. The greatest defense against predators is in numbers. That being said, it is a natural instinct to want to be around other cattle, which makes separating a cow(s) harder than moving the entire group as they want to stay together. This behavior has its advantages and disadvantages depending on the objective we wish to achieve. Moving cattle into a new pasture is as easy as applying pressure towards whichever direction we want them to go, whereas isolating a single calf requires interfering with an instinctive will to return to the group.

Aside from herd instinct, all prey animals have a heavy sense of “fight or flight”, known to the medical field as the Sympathetic Nervous System. In all cattle, the “flight” response is much stronger. We extort this instinct in order to achieve our goal of movement by entering what is widely referred to as the “flight zone”.

The Flight Zone varies on most cattle, but it is easy to gauge. When something approaches a cow, the first thing you will notice is the cow will look at it and/or turn and face it. This is part of a Parasympathetic Nervous System response which can be called “freezing”, it basically is threat assessment. If the object gets closer, the cow makes the mental threat assessment and the Sympathetic Nervous System kicks in causing the Fight or Flight, a large majority of the time the cow goes to flight and will distance themselves from the object. In my experience, the more wild cattle’s flight zone tend to be close to a ropes length, or thirty feet, whereas the handled and domesticated cattle tend to be less than ten feet.

Now, let’s discuss the process of moving a cow:

This leads us to moving the cow. When we approach the target cow(s) with our horse, the threat assessment is instantaneous and the cow(s) will most likely move away from us. This is where our objective comes into play and we must start to make choices and decide where our horse needs to be. I explain to participants in our cattle clinics that cows are like mirrors: they will replicate whatever force is put into them. For example, if I walk into a cow’s flight zone, they will walk out. If I run into the flight zone, they will run. Depending on the objective, throttle control can be a blessing or a curse depending how we use it! Next comes the directionals. My old mentor taught me that cattle are moved like a pool ball. Face them straight on, they move straight back. If we need to adjust our direction, we simply position our horse to change the angle of approach knowing the cow will move straight away from where we meet the cow. Of course, this is as basic of an explanation as I can give! When actually moving a cow from point A to point B, it is not a constant action. The cow is continuously reassessing threat level and continuously reacting to pressure, making it a dynamic situation. This is where issues occur the most, once the cow is in movement. Keeping that in mind, we must continue making adjustments in our positioning to get the cow closer to our objective.

There are three things we must be able to do: start, stop, and turn. Accomplish these tasks effectively, and we can move the cow where we want it to go. Let’s break down each action!

Start is easy. All we have to do is insert our horse into the cow’s natural flight zone to spur a reaction away from us. By entering into the flight zone, we achieve movement. Depending how much force (speed) we have behind our action will define how fast the cow will move.

Stop requires applying pressure in front of the cow. This means we must reposition ourselves to be ahead of the cow’s flight zone. Seems simple, right? In a controlled environment such as an arena, it is. However in the open pasture, this can actually be quite difficult given we cannot utilize the environment around us to aid our cause. Let’s take a controlled situation like an arena for example: there are several factors of the environment that make cattle movement much simpler. Utilizing fence is the most obvious, as we can eliminate half of the cow’s flight zone just by getting the animal against the wall, or the fence. To stop a cow that is moving alongside the wall, we position our horse in in front of the cow, meaning we are applying pressure on the cow which cannot turn and flee away because the wall is in the way. This creates an effective stop. In the open, we rely on actually going around the cow in motion and reintroducing pressure from directly ahead, thus recreating a threat assessment and achieving a stop by extorting the cow’s “freeze” instinct as the cow reassesses, or with multiple horses creating our own wall with pressure from different angles.

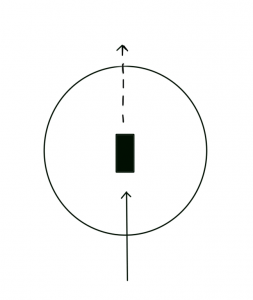

Turn happens when we redirect our pressure to either the left or the right side of the cow, causing the cow to move away from us. If we want the cow to turn left, we must apply pressure to the right side. If we want a cow to turn right, we must apply pressure to the left. How sharply we want the cow to turn determines how sharp of an angle we must use. If we stay at a 45 degree angle, the cow will move at a 45 degree angle. (see diagram).

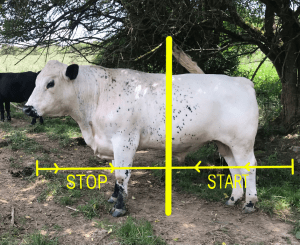

Let’s take this picture of Magnum, our British White bull, to give you a better idea of starting and stopping. This gives the best depiction of flight zones. If we draw a line that divides Magnum in half, we get two parts: a front and back half. Any pressure behind the line will result in a forward movement, and any pressure in front of the line will result in backward movement. To achieve a Start, we apply pressure behind the line. To achieve a Stop, we reapply pressure to the front of the already moving cow.

This diagram is a visual representation of the pool analogy. No matter the start point of the solid line arrow, the dotted line arrow will hold true like shown above. If we reapply the same pressure from the left side, the line will continue. Like stated above: How sharply we want the cow to turn determines how sharp of an angle we must use. If we stay at a 45 degree angle, the cow will move at a 45 degree angle.

Conclusion:

This of course is the very basics of moving livestock. The same principles apply to whether on horseback or on ground, and can be directly related to any prey animal including horses. We use the same flight zones and pressure applications with horses! All ground work is utilizing flight zones to get a response, and really all leg cues are similar. “Make the wanted action easy and the unwanted action hard” is a very common saying in horse training, and it directly applies to cattle work as well. If the cow is moving in the desired direction, there is no need to apply as much pressure. Let the cow continue the course and make adjustments as needed. If the cow strays, make the unwanted action hard by blocking the path and redirecting the cow towards where you want them to go! Developing this skill does require practice to perfect, which typically cannot be done by attending clinics alone. The best way in my opinion to develop a solid understanding of movements and flight zones is to move anything you can- other horses, goats, sheep, cows. Anything with a flight zone will strengthen your understanding and allow you to effectively accomplish your goal! To add one last comment, there are several things your horse should be able to do to effectively move cattle. A solid handle makes easy work and sharp, precise, reactive movements in the right hands makes the work easy! Moral of the story, if you want to be good at moving cattle, start with your education and then start working on your horse.

If you have any questions or would like more information, please contact us or sign up for a clinic, attend a practice, or schedule a lesson! We are happy to help you achieve whatever goals you have and answer any questions you have!